"Fresh, raw dulse has a nice minerality and tastes very much like the ocean," says Jason Ball, a research chef who works extensively with dulse at Oregon State University's Food Innovation Center in Portland. "But when you pan-fry it, it takes on a lot of those smoky and savory characteristics that are very, very similar to bacon."

Ball is experimenting with ways to incorporate dulse (rhymes with "pulse") into commercial food products that could be on store shelves as soon as this fall. But more on that later—first, the basics.

Dulse is a seaweed—a large category of edible saltwater plants and algae that also includes species such as nori and kelp. Like all edible seaweed, it provides a wealth of fiber and protein, and it's also rich in vitamins, trace minerals, healthy fatty acids, and antioxidants. It resembles a leafy, red lettuce, and grows wild on the northern Atlantic and Pacific coasts, where it's typically harvested during low tide from early summer to early fall. Unless you know someone who harvests wild it, you likely won't be able to buy it fresh—once harvested, it's normally dried immediately for maximum freshness before it's packaged. You can find dried form products from brands like Maine Coast Sea Vegetables at well-stocked grocery stores such as Whole Foods. Look for whole-leaf and flaked, powder, and seasoning mixes.

Wild dulse has long been a staple of diets in parts of northern Europe like Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. But the seaweed can also be cultivated, and professor Chris Langdon at OSU is doing just that with a patented strain of it that doesn't depend on the tides or seasons and is growable year-round (though it's not commercially available yet).

Ball, a Nordic Food Lab alum, has been cooking with dulse delivered from Langdon's facilities for months, experimenting with all kinds of ways to make the nutrient-dense sea vegetable tantalizing to even the most seaweed-averse eaters. Some of his more out-there creations included a sourdough bread with it substituted for salt; beer brewed with dried one instead of hops, an instant ramen with a dulse spice packet, a trail mix with dulse-and-banana fruit leather, smoked dulse popcorn brittle. Oh, and let's not forget about the dulse ice cream. In taste tests, Ball says the big winners were a puffed dulse rice cracker ("it's like a vegetarian chicharrón") and a dulse salad dressing made with soy sauce and rice wine vinegar.

"My dad is this old guy from the Midwest who only eats meat and potatoes," Ball says. "If I give him a handful of dulse, he's just gonna look at me like I'm crazy. But if I give him chips, something he's familiar with, they could be a gateway."

Ball is currently working with a contractor to commercialize this seaweed salad dressing and get it on shelves at a Portland food retailer by the middle of fall. Meanwhile, Langdon, who currently cultivates about 20 to 30 pounds of it weekly, is looking into moving some of the operations to eastern Oregon to up the production to 100 pounds a week.

As we've mentioned, you're most likely going to be buying and cooking dried harvested dulse, not the fresh stuff. Its nutritional value doesn't degrade after it's converted into powder or flakes, so choose the product that's most convenient for you. Store it in a dry and dark place (it'll last for at least two years), and before cooking pull apart the dulse fronds to make sure they're not housing any pebbles or other foreign matter.

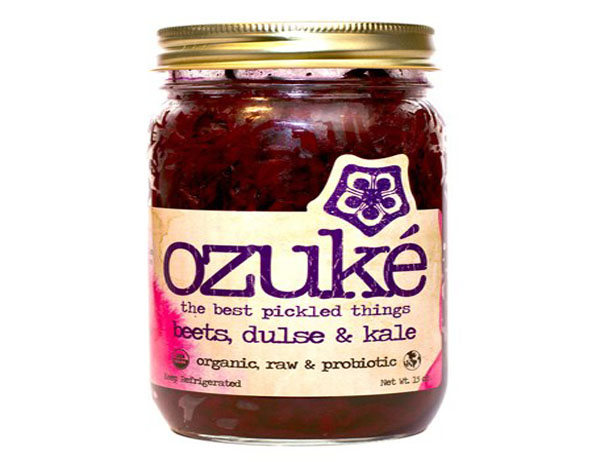

To achieve that bacon-like effect, pan-fry some dried whole-leaf dulse with oil over medium-high heat until crisp, then slap it between two slices of bread with lettuce, tomato, and mayonnaise for a DLT. Eat raw or cooked it as a snack, or add it to sandwiches and salads. Try a little flakes sprinkled over scrambled eggs or popcorn, or mixed into vinaigrettes. If you're feeling truly seaweed-shy, start with a product that has a manageable quantity of dulse in it, like Ozuké's pickled beets with dulse and kale (grab a jar of their umeboshi plums while you're at it). And on the opposite end of the spectrum, if you're feeling extra-bold, add a small scoop of dulse powder to smoothies for a creamy seaweed shake.

"People have this negative idea of seaweed, but I would love for dulse to be as ubiquitous as mushrooms or tomatoes," Ball says. "I think we're on our way."

We have Dulse as marine ingredients available on https://seatechbioproducts.com/dulse-palmaria-palmata-human-nutrition-powder-25kg.html

Source: http://www.bonappetit.com/test-kitchen/ingredients/article/dulse-seaweed